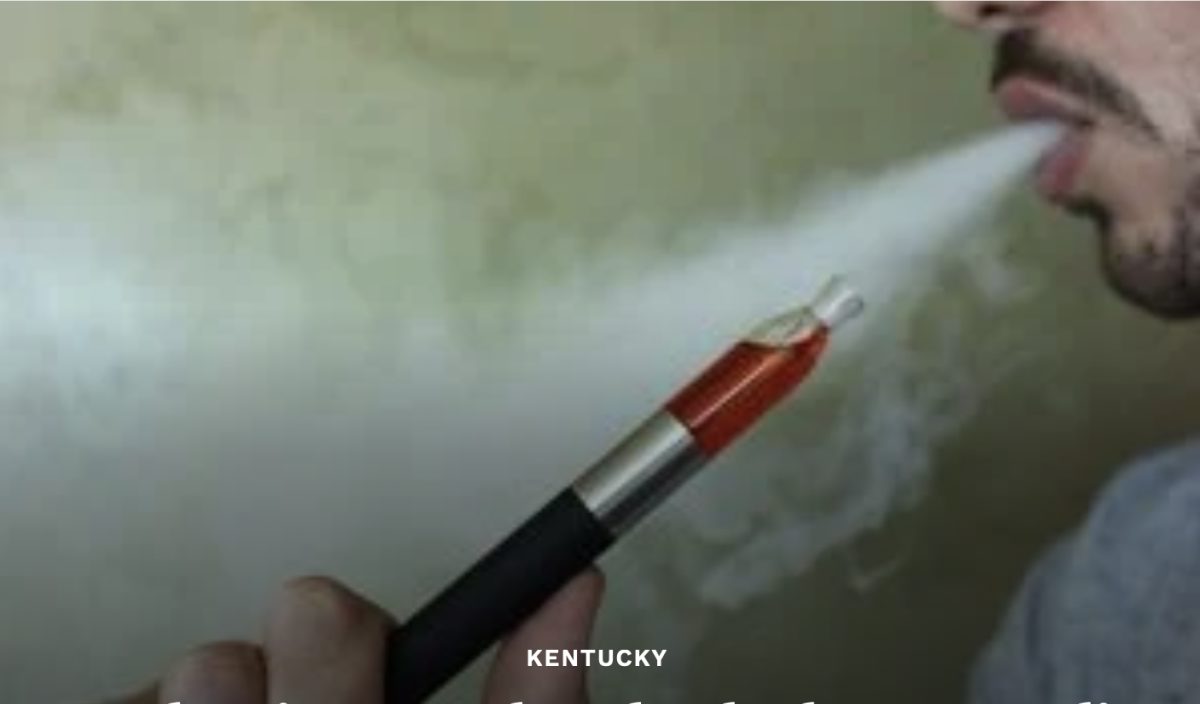

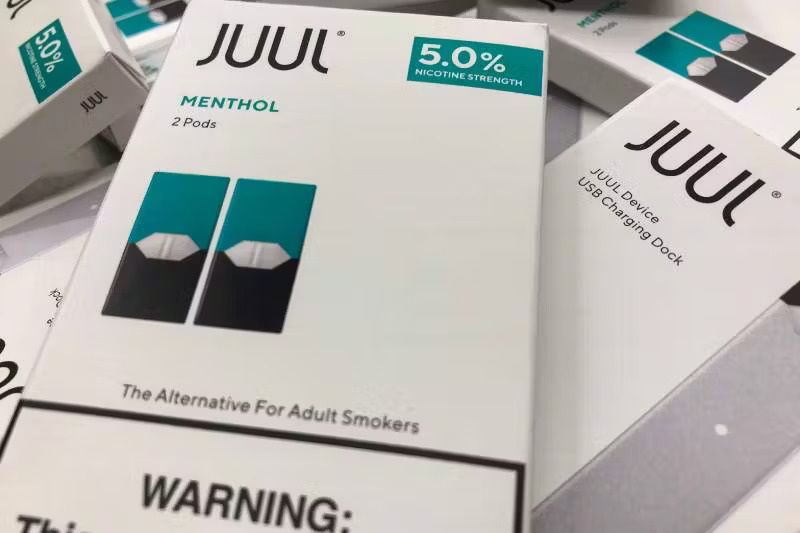

In 2015, my now-and-then smoking habit had crept up to two or three cigarettes per day, and a lot more when I was drinking. After one tobacco-laden weekend resulted in a full week of phlegm and coughing, I felt like I had to do something. I was working in Times Square at the time. From the window outside my cubicle, I was face to face with video billboard playing the painfully hip new commercial from the e-cigarette company Juul. Turns out: marketing works. Before I knew it, I’d ordered one for myself and fallen in love at first hit. Everything about the e-cigarette seemed, and felt, better than my old cancer sticks. The smell, the cost, the surprisingly strong amount of nicotine it delivered per hit. At the same social events where I once belched noxious, girlfriend-repelling, shirt-stinking tobacco fumes, I was now puffing crème brûlée-scented fog clouds.

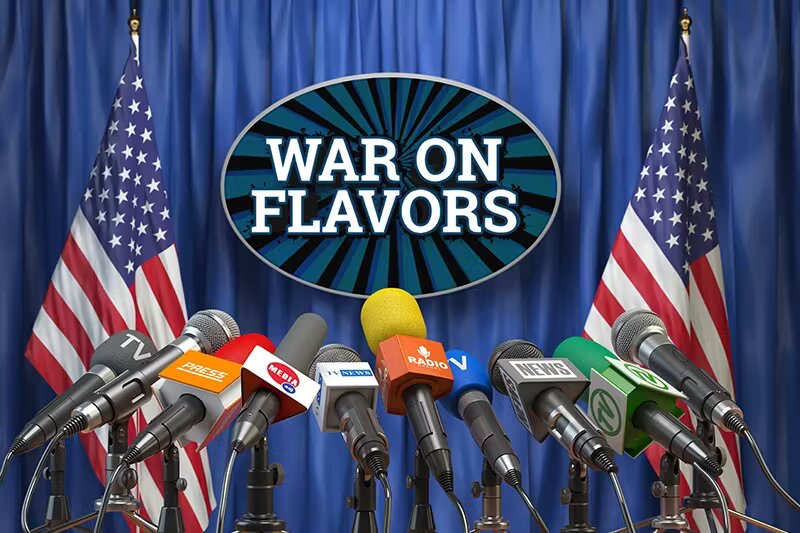

E-cigarettes have been around since 2003 and we still don’t know much about their health effects or safety. But, as we’ve pulled the flavored smoke from our Juuls and similar vaporizers, we’ve blindly assumed one thing: they have to be a better idea than benefit of quitting smoking cigarettes.

Cigarettes might be the least controversial enemies of your health. They cause cancer, emphysema, heart disease, even impotence. While saturated fat and alcohol still have their supporters, nobody is rushing to cigarettes’ defense.

When people voiced health concerns, I came to my Juul’s defense. If you’re going to smoke it’s clearly better to go with e-cigarettes. In fact, the U.K.’s Public Health England had published a review concluding vaping was 95 percent less harmful than smoking. A Greek study had found 81 percent of people in a group of over 19,000 had successfully used e-cigs to quit. I’d heard (and inhaled) enough. This was the answer.

It was the wrong one.

Over the next few years, the optimism over e-cigarettes waned as their popularity skyrocketed. Juul’s sales increased over 600 percent each year to become the best selling device on the market while I inhaled an atmosphere’s worth of vanilla vapor into my lungs. I never kidded myself into thinking that this habit was harmless, but my conviction that they were less harmful than cigarettes made the endeavor seem worthwhile, even praiseworthy.

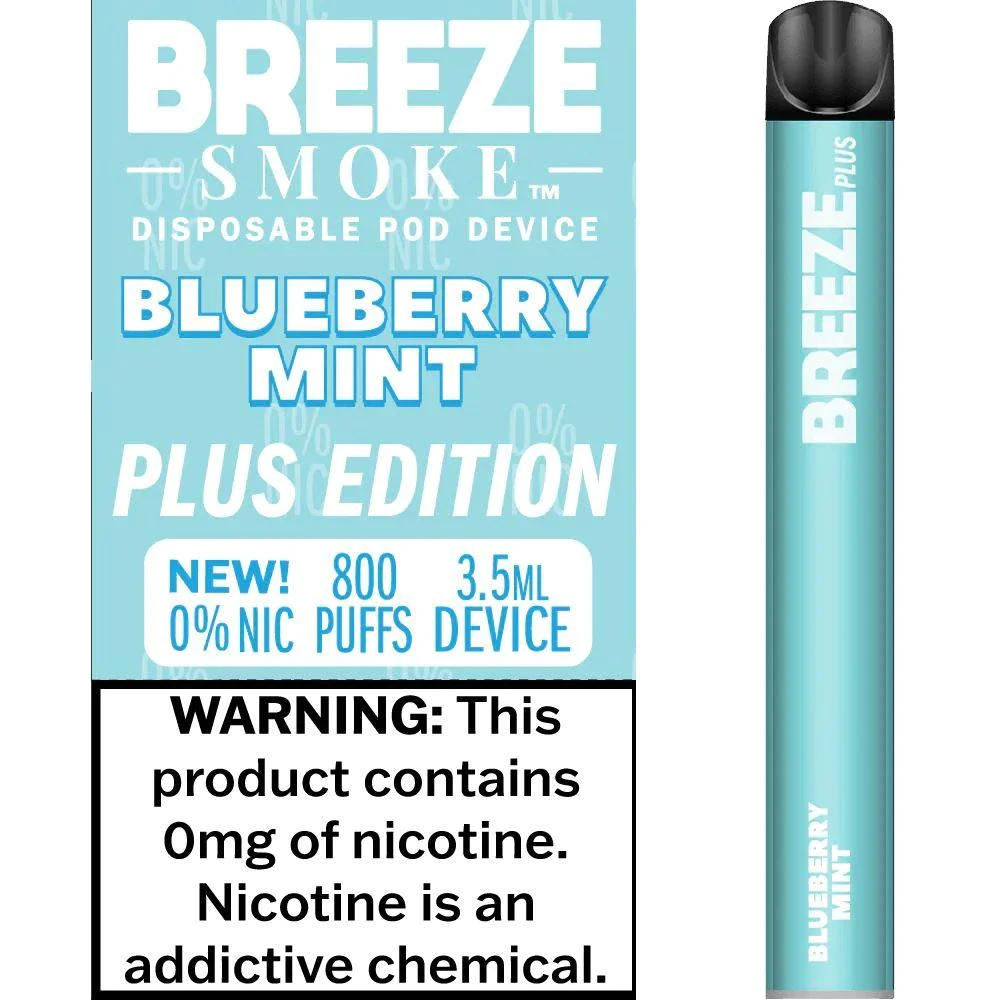

After all, the average cigarette has some 4,000 chemical compounds, including dozens of confirmed carcinogens, while my e-cig cartridges contained just five: distilled water, nicotine, glycerin, propylene glycol, and some flavoring.That’s a flimsy argument: “something with lots of scary chemicals is less dangerous than something with just a few scary chemicals.

Firstly that propylene glycol, largely responsible for making your breath look like a cloud of mist, is also found in fog machines used in concerts and has been linked to chronic lung problems among stagehands. It’s actually FDA-approved for use in food (believe it or not it’s common in pre-made cake mix) but when heated to vaping temperature it can produce the carcinogen formaldehyde.

In other words, just because something is safe to eat doesn’t mean it’s safe to be inhaled. (Duh.) Vaping also seems to trigger potentially harmful immune responses in the lungs. It’s not just tasty air.

0